Een prachtig blog van een Amerikaanse medisch studente over de noodzaak van emotionele intelligentie en het voelen en erkennen van je emoties als arts. Met dank aan @KevinMD

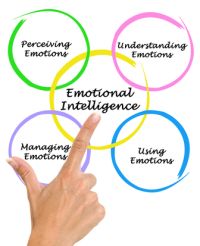

A popular teacher at our school recently gave a lovely talk about “emotional intelligence.” I was at once proud of my school for offering such a lecture and disturbed that it was necessary. Our schedules are flooded with lectures devoted to issues such as professionalism and emotional awareness. We’ve all heard stories about insensitive doctors with terrible bedside manner and outrageous faux pas by medical students, transmitted in whispers, and we debate whether they are urban legend or fact. It leads me to wonder, what percentage of med school students actually are as socially awkward and unaware as we are led to believe? Most of the med students I know are caring and compassionate people.

We all have our limits and we can be clouded sometimes by exhaustion and frustration. But cracking under pressure now and then does not negate the fact that this is a group of uncommonly good-hearted people. So I have to wonder, where are things breaking down between that image, and the idea that we are self-centered individuals who are out of touch with reality? I suspect that only a minority fall in the latter group. It’s undeniable, however, that some young doctors grow disillusioned and forget how be human. That image is so disturbing that it is burned into the brains of those scorned and misunderstood by their doctors, and in the eyes of society, we have fallen. This is our burden to carry.

If we are denying our emotions and our humanity, perhaps it is not that we are callous individuals but that we are scared. Med students are faced with many inhuman tasks. So far during medical school I have befriended a dying woman and watched her slowly decline, dismembered a cadaver, cut into the flesh of a live human, inserted catheters, poked people with needles, performed pap smears and rectal exams, removed staples, packed seeping wounds, sewed together bleeding skin, even helped to deliver babies. When I first learned a couple of years ago that I would eventually have to do all these things, I had a panic attack. At that point I was squeamish looking into a classmate’s ears. Yet they became necessary and even routine elements of some of my classes.

Maybe it’s not just about the exhaustion and the fact that our brains are crammed with a bunch of scientific details and Latin-based vocab words. We do profound things without hesitation, without letting a glimmer of weakness pass across our faces, because we have to. It’s not an option. Thus, some degree of detachment is essential to survival. When we become pros at keeping our emotions under control, trying not to let anyone see our hands shake or sweat roll down our foreheads, it’s not a surprise that we become a little mixed up. Personally I wonder what would happen if medical schools not only offered but required routine mental health checks for their students. At this point, there is no safe place for us to admit when we feel scared, shocked, dehumanized. We are rarely reminded that acts such as assisting a surgeon and delivering a baby are not normal, they are extraordinary, and we are extraordinary for making the sacrifices and finding the strength necessary to be a part of it all. Instead we suppress these emotions and tell ourselves that if other classmates can get through without being scared, we must be weak for feeling that way. And just like that, we have lost touch with reality.

I’m ashamed to say, sometimes even I find myself asking how much emotional intelligence actually matters. The time that I spend writing and ruminating can feel self-indulgent. This was particularly true during first and second years, when memorization and the ability to sublimate bodily urges (eating, sleeping, having fun) in order to study longer were the path to an “honors” grade. Third year is more about relationships and personality and the ability to connect with others. And I am starting to see how having emotional intelligence is what makes a doctor great with patients. After seeing hundreds of patients this rotation, one after another, I am learning to see the subtle emotions that flicker across people’s faces. I am learning to detect when people are really in danger, and I have missed things the real doctor later picked up on because I failed to read these cues. One of my teachers used to say that we must learn to recognize when someone looks sick. Sounds simple but takes great perception. And usually that judgement can reveal more than a lab test or a CT scan.

Emotions play a large role in my life. Rather than hiding from them, denying them, I try to understand how the world affects me, how I handle challenges, how the people I interact with make me feel. My major decisions are based not on logic but on how I feel. I understand that this is not entirely normal. Emotions are inconvenient sometimes. They can draw you into a black hole. But that does not mean that they should be avoided completely. Delivering a baby or performing a surgery is not just “cool,” it is amazing. Miraculous. It is only when you open your heart to all emotions – the sadness, the disappointment, the wonder, the joy – that those moments become so potent.

I applaud our educators for acknowledging that emotional intelligence matters, because it does. I am glad they take time out of orientation days to remind us of its importance. I am now sending out a plea to my fellow classmates: let’s show everyone that they don’t need to. Don’t be afraid to admit to yourself or to a loved one that you have an emotion. This is not a sign of weakness, but of being human. We are set apart from plants and fungi by our beating hearts, our breathing lungs, and the ability to feel complex emotions. Celebrate this. Feel giddy when you deliver a baby or take out a cancer. Feel sad when you witness suffering. Learn to read the faces of your patients, to gauge what they are really feeling. It means nothing and sometimes, it means everything.

Molly McPheron is a medical student who blogs at Indiana University School of Medicine’s Tour the Life.